|

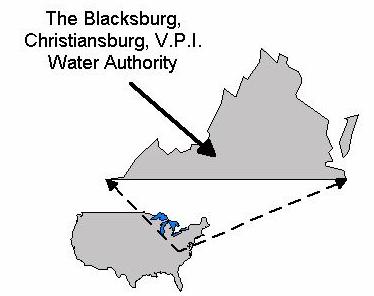

The Blacksburg · Christiansburg · V.P.I. Water

Authority

by Austin Hill Shaw (ashaw@vt.edu)

Hee-Chae Lee

(koma@vt.edu)

Behind the potable, palatable water that all of Virginia Tech and the surrounding communities

depends upon daily, is the Blacksburg,

Christiansburg, V.P.I., Water Authority. Established in 1954 and constructed

in 1957, the Water Authority has been treating an average of six to seven

million gallons of water a day. The Water Authority deals solely with drinking

water and is not involved in waste water treatment. Operating 24 hours a day, 7

days a week, the Water Authority runs a lean operation, staffing only 12 people

to run the entire facility. Despite this, using automated and manual methods,

the water is tested on average 249 times a day in and around the plant to ensure

it is fit for consumption. These test can be divided into two broad categories:

test for contaminants and tests for physical parameters. The contaminants

include such things as pesticides, metals, and parasites; substances that can

adversely affect the health of the consumers. The physical parameters, such as

temperature, turbidity, pH, salinity, and odor tests are used to determine the

amount of certain chemicals that will need to be added to successfully treat the

water for the lowest cost possible.

Behind the potable, palatable water that all of Virginia Tech and the surrounding communities

depends upon daily, is the Blacksburg,

Christiansburg, V.P.I., Water Authority. Established in 1954 and constructed

in 1957, the Water Authority has been treating an average of six to seven

million gallons of water a day. The Water Authority deals solely with drinking

water and is not involved in waste water treatment. Operating 24 hours a day, 7

days a week, the Water Authority runs a lean operation, staffing only 12 people

to run the entire facility. Despite this, using automated and manual methods,

the water is tested on average 249 times a day in and around the plant to ensure

it is fit for consumption. These test can be divided into two broad categories:

test for contaminants and tests for physical parameters. The contaminants

include such things as pesticides, metals, and parasites; substances that can

adversely affect the health of the consumers. The physical parameters, such as

temperature, turbidity, pH, salinity, and odor tests are used to determine the

amount of certain chemicals that will need to be added to successfully treat the

water for the lowest cost possible.

As a water treatment plant, The Blacksburg, Christiansburg, V.P.I. Water

Authority is unique in that it is neither a privately owned treatment system,

nor is it a public municipality. Around the United States, most water treatment

plants fall into one of these two broad categories. Privately owned systems are

required to pay taxes on the water they sell and sometimes must compete with

other privately owned water treatment operations. On the other hand, public

municipalities are sometimes neglected due to their control by elected

officials, who sometimes fail to maintain facilities in face of more politically

charged projects. Walking the line between a private facility and a

municipality, the Water Authority is a tax exempt organization governed by a

representative from each of the three served areas, plus two additional

representatives the three districts agree upon. The Water Authority pays for the

cost of operation by wholesaling their water for $1.06 per thousand gallons to

the three districts and not through tax collection. Thus, the Water Authority

doesn't have to rely on tax revenues because they are wholesaling the water to

cover their operating expenses; they don't have to compete with privatized

treatment plants; they are immune from the deleterious affects of political

cycles and, in addition, the Water Authority maintains the right to condemn

property as needed. As Superintendent Jerry Higgens puts it, "our situation is

ideal."

As a water treatment plant, The Blacksburg, Christiansburg, V.P.I. Water

Authority is unique in that it is neither a privately owned treatment system,

nor is it a public municipality. Around the United States, most water treatment

plants fall into one of these two broad categories. Privately owned systems are

required to pay taxes on the water they sell and sometimes must compete with

other privately owned water treatment operations. On the other hand, public

municipalities are sometimes neglected due to their control by elected

officials, who sometimes fail to maintain facilities in face of more politically

charged projects. Walking the line between a private facility and a

municipality, the Water Authority is a tax exempt organization governed by a

representative from each of the three served areas, plus two additional

representatives the three districts agree upon. The Water Authority pays for the

cost of operation by wholesaling their water for $1.06 per thousand gallons to

the three districts and not through tax collection. Thus, the Water Authority

doesn't have to rely on tax revenues because they are wholesaling the water to

cover their operating expenses; they don't have to compete with privatized

treatment plants; they are immune from the deleterious affects of political

cycles and, in addition, the Water Authority maintains the right to condemn

property as needed. As Superintendent Jerry Higgens puts it, "our situation is

ideal."

The Water Treatment Process

The Water Treatment Process

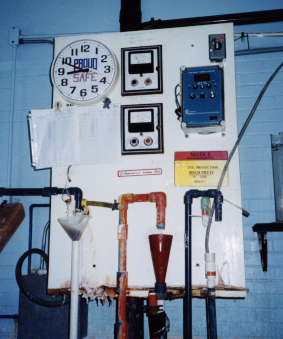

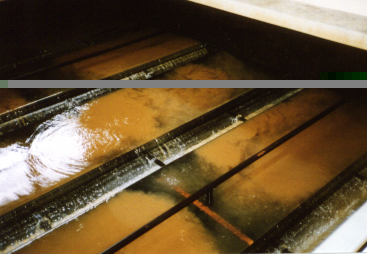

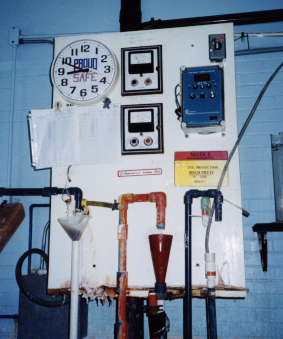

The process begins with raw water being pumped out of the New River. The

water is filtered though large screens which prevent large objects from entering

the treatment system and damaging the equipment therein. The water is analyzed for turbidity and pH automatically so appropriate levels

of chemicals may be added further along in the treatment process.The raw water

is pumped into the flash mix basin, a turbulent well mixed environment. Before

the raw water enters this area it is injected with chlorine gas, sodium

hydroxide, and polyaluminum chloride (PAX). These three chemicals are used for

the sterilization of the water, the adjustment of pH to hinder corrosion in

pipes, and to begin the coagulation process respectively. PAX promotes the

process of coagulation by creating chemical attractions between particles due to

the presence of the aluminum ion in the water. As the name implies, the primary

purpose of the flash mix basin is to distribute the added chemicals evenly

throughout the water.

The water is analyzed for turbidity and pH automatically so appropriate levels

of chemicals may be added further along in the treatment process.The raw water

is pumped into the flash mix basin, a turbulent well mixed environment. Before

the raw water enters this area it is injected with chlorine gas, sodium

hydroxide, and polyaluminum chloride (PAX). These three chemicals are used for

the sterilization of the water, the adjustment of pH to hinder corrosion in

pipes, and to begin the coagulation process respectively. PAX promotes the

process of coagulation by creating chemical attractions between particles due to

the presence of the aluminum ion in the water. As the name implies, the primary

purpose of the flash mix basin is to distribute the added chemicals evenly

throughout the water.

Flash Mix Basin Chemical Feeder(Image)

Next

the water flows into two separate flocculation basins and mixers. The conditions

are far less turbulent but the water remains well stirred. The water remains in

these two separate, but identical treatment paths, until the they converge again

at the clear wells which mark the final stage in the treatment process. In the

flocculation basins and mixers, large low speed paddles stirs the chemically

treated water. Suspended solids in the presence of PAX form larger and larger

clusters of particles, known as flocs, as the water is slowly stirred. As the

flocs grow in size as additional particles latch, they also become heavier,

which is crucial for the next step in the treatment process to be successful. Next

the water flows into two separate flocculation basins and mixers. The conditions

are far less turbulent but the water remains well stirred. The water remains in

these two separate, but identical treatment paths, until the they converge again

at the clear wells which mark the final stage in the treatment process. In the

flocculation basins and mixers, large low speed paddles stirs the chemically

treated water. Suspended solids in the presence of PAX form larger and larger

clusters of particles, known as flocs, as the water is slowly stirred. As the

flocs grow in size as additional particles latch, they also become heavier,

which is crucial for the next step in the treatment process to be successful.

Settling Basin Animation

The water with its well formed flocks flows from the flocculation basins into

the settling basins, an environment almost devoid of turbulence which is

designed as a plug flow reactor. The water takes a minimum of 3 hours to cross

the settling basin and during that time, the flocs settle out of the water and

collect at the bottom. Twice a year, the basins are drained and using

pressurized water, the flocs at the bottom are pushed out to the settling pond

below the plant. In the settling ponds, water from the settled solids and from

the backwash (described later) is allowed to discharge into the steam. After the

water has left the settling basins, most solids have settled out.

The water with its well formed flocks flows from the flocculation basins into

the settling basins, an environment almost devoid of turbulence which is

designed as a plug flow reactor. The water takes a minimum of 3 hours to cross

the settling basin and during that time, the flocs settle out of the water and

collect at the bottom. Twice a year, the basins are drained and using

pressurized water, the flocs at the bottom are pushed out to the settling pond

below the plant. In the settling ponds, water from the settled solids and from

the backwash (described later) is allowed to discharge into the steam. After the

water has left the settling basins, most solids have settled out.

The final step in removing particles takes place in the dual media filters. The

water that has left the settling basins filters through a matrix of anthracite

coal, sand, and gravel. The fine particles that did not settle out in the

previous treatment steps, become trapped in the filter, the smallest particles

being trapped at the interface of the coal and the sand where porosity is at a

minimum. The clean water proceed through the filter to the clear well below.

According to regulations, whenever readings show a turbidity of 0.1 in the water

exiting the dual media filters, or there is a head loss of 6.5 feet, or 100

hours elapses, which ever comes first, the dual media filters must be cleaned.

By forcing clean water from the clear well back up through the filter, the

matrix is disturbed and fine particles are flushed out of the system. This

process is called backwashing.

The final step in removing particles takes place in the dual media filters. The

water that has left the settling basins filters through a matrix of anthracite

coal, sand, and gravel. The fine particles that did not settle out in the

previous treatment steps, become trapped in the filter, the smallest particles

being trapped at the interface of the coal and the sand where porosity is at a

minimum. The clean water proceed through the filter to the clear well below.

According to regulations, whenever readings show a turbidity of 0.1 in the water

exiting the dual media filters, or there is a head loss of 6.5 feet, or 100

hours elapses, which ever comes first, the dual media filters must be cleaned.

By forcing clean water from the clear well back up through the filter, the

matrix is disturbed and fine particles are flushed out of the system. This

process is called backwashing.

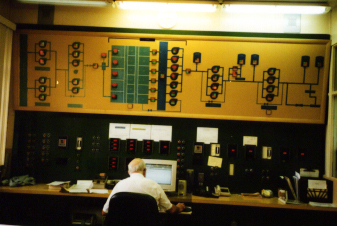

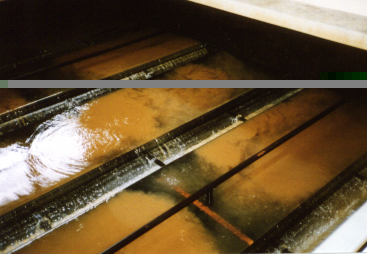

Backwashing in progress

The backwash water with the fine particles in suspension, exits over a baffle

and out to the settling ponds. The matrix is then reestablished simply by

allowing the different sized particles within the matrix to settle back out in

order of there respective densities. In the settling ponds, the solids from both

the settling basins and the backwash are allowed to settle out while the excess

water drains off to the New River.

The backwash water with the fine particles in suspension, exits over a baffle

and out to the settling ponds. The matrix is then reestablished simply by

allowing the different sized particles within the matrix to settle back out in

order of there respective densities. In the settling ponds, the solids from both

the settling basins and the backwash are allowed to settle out while the excess

water drains off to the New River.

The final step in the treatment process occurs in the clearwell were the

filtered water is collected and disinfected below the dual media filters. As was

said earlier, the disinfection process really begins at the flash mix basin,

where the entering water is injected with chlorine gas. After settling and

filtration, the water is now almost devoid of suspended particles. But

pathogenic organisms and other organic substances may still remain in the water.

While organics can make the taste and odor of the water undesirable, the

presence of certain pathogens can cause sickness and even death to consumers. In

the clearwells, additional chlorine gas is dissolved into the water. This

dissolved chlorine oxidizes both the pathogens and organics and leaves the

waters safe and desirable to drink. The Water Authority also adds additional

chlorine to protect the water from contamination on its path from the plant to

the consumer.

Chemical Storage Tank

Once the water has been disinfected in the clearwell, it is suitable for

consumption. However, to inhibit the corrosion process in the pipes of the

communities, pH is adjusted if need be using sodium hydroxide to make the water

slightly basic. In addition, as water leaves the clearwell, zinc orthophosphate

is added to further retard corrosion. The finished water then makes its way

through a series of pumps, pipes and reservoirs to storage tanks in the three

surrounding communities. The water in the distribution system is under pressure

so that opening any tap in the community will yield safe, pleasant water for

consumption.

Acknowledgements

The majority of the

information for this web page was gathered during an interview with the Water

Authority's superintendent, Jerry Higgens. The interview and tour of the plant

took place on Thursday, October 16, 1997. Additional information was gathered

via telephone conversations with Jerry Higgens and various employees of the

plant. The authors of this web page would like thank Jerry Higgens and all those

at the Water Authority who helped to make this web page possible.

Send comments or suggestions to:

Student Authors: Austin Hill Shaw and

Hee-Chae Lee

Faculty Advisor: Daniel Gallagher, dang@vt.edu

Copyright © 1997 Daniel

Gallagher

Last Modified: 2-14-1998 |